China's 'Great Green Wall' brings hope but also hardship

Inner Mongolian herder Dorj looked bitterly at the vast grasslands where his flock once grazed freely, before the practice was banned as part of a massive Chinese state greening project.

Restrictions on traditional grazing are a key part of China's "Great Green Wall" campaign, a decades-old anti-desertification project credited with "greening" over 90 million hectares.

The campaign initially aimed to contain the expansion of deserts in the arid north caused by intensive farming, grazing, mining and climate change.

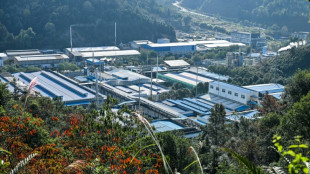

But in some places the goal has now evolved into creating new arable land, and the project combines large-scale tree planting with sowing drought-resistant creepers, and even installing vast solar arrays to limit wind and shade plants.

China has lately touted the project at international meetings, and President Xi Jinping last week pledged to increase forest cover to help meet climate goals.

Planting the equivalent of 840,000 football pitches around Inner Mongolia's Kubuqi desert has created tens of thousands of jobs and helped alleviate poverty, a 2015 United Nations study found.

But for some ethnic Mongolians, who make up 17 percent of the autonomous region's population, the campaign has eroded traditional farming practices and culture.

Dorj's herd -- now reduced to around 20 sheep -- is confined to a fenced area around his brick home that he says is too small and sparse.

In the Kubuqi desert, herders have paid the price for fixing habitat degradation they did not cause, said Enghebatu Togochog, a Mongolian activist living in exile in the United States.

The measures "have forcibly displaced herders, severing their connection to the land and disrupting sustainable practices that maintained the grasslands' delicate balance for millennia".

Traditional nomadism in Inner Mongolia effectively vanished ten years ago, he added.

When AFP visited, reporters were followed by men who said they worked for local authorities throughout their trip, impacting their ability to speak to other herders.

- Overestimated impact? -

In a 2017 article, Chinese researchers acknowledged that the effect of grazing on desertification in China might have been overestimated.

They pointed to other factors, including still-prevalent mining, intensive agriculture, and climate change.

The ban on free grazing, and the introduction of dedicated patrols to enforce it, has triggered regular protests by herders and several arrests, according to academics and NGOs.

Togochog says the greening project is "part of the overall project of just completely changing the Mongolian landscape" and traditional way of life.

"The sole beneficiaries are the Chinese -- especially the state, the companies," he said.

Neither Elion Resources Group -- the Chinese company in charge of the Kubuqi project -- nor the local municipality replied to AFP's request for comment.

Experts say greening projects should avoid non-native and water-intensive plants.

"A plant that consumes too much water can deplete the water table and lead to further degradation," said scientist Zhang Yanping as she took samples from pines and poplars planted a decade earlier in the Kubuqi.

And the instinct to convert desert into greenery is not always the right one, said Wang Shuai, a geography professor at Beijing Normal University.

"Deserts have important ecological functions, like water conservation and biodiversity," he said.

"It's not necessary to eliminate them... (just) to prevent their expansion."

- 'Everything was desert' -

Around the newly greened areas, large billboards display a slogan by President Xi extolling the Great Green Wall's philosophy: "Clear waters and green mountains are as valuable as gold and silver mountains."

Between 2016 and 2050, the state aims to plant another 70 million hectares, an area the size of continental France, according to official documents.

China's largest desert, the Taklamakan, is now completely surrounded by vegetation, according to the forestry administration.

The project is credited with helping boost the average income of local farmers and herders, including Mongols, the UN report found.

Several kilometres west of Dorj's house, farmer Bai Lei gently eased from the sand a Cistanche -- a parasitic plant prized in traditional Chinese medicine.

"Before, everything here was desert," she said, proudly gesturing at fields full of corn and sunflowers.

Bai, from China's Han majority, started her business over ten years ago.

Cistanche is particularly well suited to fighting desertification, she said -- it grows on the roots of other plants, anchoring its host.

Around Bai's farm in Dengkou county, more than 90 businesses grow the fleshy, yellow-flowered herb, according to state media.

Tourism is also now thriving in the desert.

Feng, a Han former farmer who only gave his surname, now runs a busy quadbike rental business in an area undergoing greening.

He said the grazing ban helped increase available pastures, and that grazing was allowed in areas once plants matured enough to produce seeds.

"Resources are more abundant, and our lives are more prosperous," he told AFP.

"We can hold our heads up with pride."

R.Campbell--PI